The perks of a high-documentation, low-meeting work culture

By Kate Monica●5 min. read●Oct 9, 2024

At Tremendous, we practice meeting mindfulness through an intentional high-documentation, low-meeting work culture.

This is a culturally influential decision considering that we’re a remote-first company. We don’t see each other in passing in the office, and we don’t have lunch together.

It may seem counterintuitive to cut down on face time if you rarely see your colleagues as it is. But it’s working for us, and there’s a few reasons why.

Practicing meeting mindfulness allows us to free up time for other stuff that matters more. This isn’t to say that all meetings are useless — it’s just that the meetings we do have at Tremendous are meetings for a reason.

We don’t schedule meetings for quick status updates or aimless, recurring check-ins. And we don’t host Zoom happy hours or other manufactured social situations. (We save that for our twice-annual offsites, our most recent being September in Mexico City.)

We do have meetings to discuss particularly heated topics and succinctly communicate ideas on projects that require high-bandwidth collaboration.

Our low-meeting culture allows us time to do high-value tasks. Our high-documentation culture is the secret sauce that makes us more productive, transparent, thoughtful, scalable, and efficient.

We couldn’t afford to cut down on meetings if we didn’t document our thought processes, decisions, and projects so diligently and openly. At times, it does seem like a lot of work. But it pays dividends, and you can write whenever you like.

The following are five discrete benefits to a high-documentation, low-meeting culture that we’ve seen first-hand at Tremendous. But the intangible, overarching benefit of practicing meeting mindfulness is this: you spend less of your day sort-of-listening and more of your day really thinking.

Table of contents

Get things done

One of our values at Tremendous is autonomy. We want our people to feel they have the independence and freedom to make decisions about their own work.

When people feel they can make decisions on their own without waiting on four bureaucratic tiers of approval, they can get things done faster.

Our low-meeting culture is integral to giving people the space and time they need to make innovative decisions.

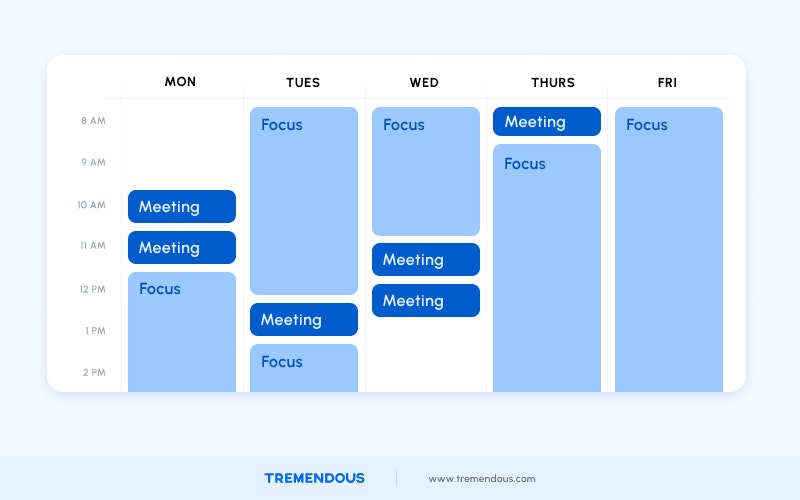

Doing creative, cognitively-intense work requires a fair amount of free time. At Tremendous, we target planned collaboration to a single window of time each day: 12pm to 3pm EST.

That way, we give our teams the time to focus on high-value tasks uninterrupted for the remainder of their workday.

There are risks inherent to a more autonomous work environment: greater autonomy can bring greater chaos.

However, a little bit of disorder is a reasonable price to pay for increasing the speed and diversity of decision-making across the organization. While this opens the door for people to sometimes make the wrong decision, mistakes are part and parcel of real innovation.

Plus, most of our projects are asymmetric bets with high upside and low downside, so even if something doesn’t pan out as expected, risk is low.

While we are a high-documentation culture, we’re also low-process. Rather than bogging down innovative thinking with layers of administrative work and approvals, we encourage people to move fast.

Allowing for this high degree of autonomy means we need to place a lot of trust in our employees. We trust them to use their time wisely, and we trust them to make good decisions.

But we take great care during the hiring process to choose people that thrive under these conditions.

A tangential bonus of creating an autonomous culture where people are free to devote most of their day to cognitively-intense work is that Tremendous attracts the right kind of talented people.

People who want to spend the majority of their day thinking and working tend to be contemplative and creative. This further perpetuates a culture of autonomy, intentionality, and diversity of thought.

Make thoughtful decisions

Intentionality is another one of our core values: we want everyone to put thought and care into every impactful decision they make at work.

This is especially applicable when it comes to meetings. Scheduling a meeting is an action that affects the workflows of several people. The way one person plots out their day has a direct impact on their productivity and output.

It’s not just about the meeting, which is itself a thirty to sixty-minute intrusion on someone’s day. It’s about the time wasted anticipating a meeting, where people feel they don’t have the time to plunge into an important project.

It’s also about the 15 or so minutes after the meeting when people are reorienting their frame of mind to tackle the problems they were focused on before the interruption.

That’s to say nothing of the time and cost expense associated with running a meeting and doing follow-up afterwards. All of this takes time. And time is a valuable, finite resource.

Urging people to schedule meetings with intentionality is one side of the coin. The other side serves as the impetus for our high-documentation approach.

For every piece of substantive output, the first step is to create a doc explaining the problem they want to solve, the options they considered, and the ‘why’ behind the recommended approach.

We craft these documents with a focus on depth and quality. Our design briefs, technical briefs, strategy docs, competitive research, and persona docs include thoroughly fleshed-out, well-written records of the complete decision-making process. They often link to and incorporate relevant threads in Slack.

We deliberately encourage people to create documents rather than build slide decks. Slide decks can mask poorly-written content with decorative font, sleek formatting, and compelling images.

In a document, the content is all you have. It forces people to focus on communicating their ideas as clearly as possible.

This focus on clarity of thought and precise language also makes working with vendors easier and more cost-effective. Vendors have access to the in-depth specifications and needs we outline in our proposal docs, so they can give us a more accurate quote.

Vendors can also more accurately identify and deliver exactly what we want in our solutions because they have the full scope of information they need to understand our pain points and goals.

Ultimately, this puts us in a position to work with higher quality vendors that make the most sense for us. They understand the way we think and where we want to go in a unique and detailed way.

This attention to detail and documentation does take a little bit of extra time and effort. But the end result is higher quality output and better outcomes.

Move long-term fast

In the same way that there’s a time and expense cost associated with a high-meeting, low-documentation culture, there’s also a cost associated with our approach.

We spend a lot of time writing. A lot more time than most other companies probably spend.

While this is quite a commitment, the resulting searchable, traceable, public record of all significant decisions, projects, and initiatives across the organization makes it way easier to onboard and scale.

It’s easier for new teammates to learn the ropes quickly when there’s a trove of existing documentation outlining the thought process behind every significant decision made at the company.

And because all of this documentation is internally public by default, people don’t need to ping each other on Slack seeking answers or permission to access what they need. They can see what info is available and then read it, further reducing workflow interruptions and increasing efficiency.

Expanding initiatives also becomes simpler when thorough documentation is publicly available to all.

If a project launched by a couple team members ends up really working, we can fold in other teams and individuals and get them up to speed fast by pointing them to the right resources.

Adopting a high-documentation culture is a concerted decision to invest time up-front to move faster in the long-term.

Learn from successes

One reason it’s easier to scale a high-documentation culture is because teammates have ample opportunities to learn from each other’s successes.

Professional development is a byproduct of having access to the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of every impactful decision the company makes.

Additionally, because all documentation and briefs are subject to peer review, anyone who creates output (read: everyone at the company) learns and grows from the evolution of their own recommendations and proposals.

We do have an important rule for commentary, though: if you have a critique, make it constructive. We prefer that people offer suggestions or improvements rather than pointing out flaws in an argument and moving on. Or as we put it, don’t be a seagull — a creature that craps all over something and flies away.

Subjecting our own ideas and suggestions to peer review can be daunting. Like our documentation, our feedback is public. We mostly offer feedback by leaving comments directly in Notion and Google docs, and sometimes as replies in Slack threads.

Egos are on the line, and the stakes feel a bit higher when you’re composing a structured proposal rather than making an off-hand suggestion at a meeting.

But feelings of discomfort are often useful. By pushing ourselves a step outside our comfort zone, we’re invited to reflect on our own decision-making process, strengthen the merits of our arguments, and make a rock-solid case for our ideas.

Reduce the hidden costs of meetings

Ultimately, a high-documentation, low-meeting approach to work lays the groundwork for a builder culture.

Having the time and space to get into a flow state is foundational to being a builder. It’s hard to program, design, or write in short bursts. A lot of people can’t do cognitively-intense tasks without a clear 3 hour or so block of time to do heads-down work.

The reason so many people struggle to do thoughtful work amidst interruptions boils down to context-switching.

Context-switching is the act of halting work on one project, performing an unrelated task, and then resuming work on the original project.

The unrelated task could be checking email, tracking down a file, or jumping onto a Zoom call. These interruptions may seem slight, but they add up.

One study from Carnegie Mellon University’s Human-Computer Interaction lab found that when you try to do two tasks at once, your performance on both tasks gets about 20 percent worse.

This loss in work quality is compounded by the time expense of context-switching: it takes the average person 23 minutes to refocus after an interruption, however small. Even a Slack ping can derail productivity.

And when these interruptions consist of largely directionless meetings, the time cost skyrockets. A 30-minute meeting scheduled in the middle of the day may inhibit an engineer’s ability to write clean code or a teammate’s ability to write up a proposal for a new initiative.

This cost is exacerbated further by the time wasted in anticipation of the meeting, as well as the time spent refocusing on the original task after the meeting. When meetings lack agendas, the efficiency cost quickly becomes grave.

Recurring meetings are also particularly vulnerable to diminishing returns: their value often decays over time because they’re scheduled by default, even when there’s nothing of note to discuss.

Conclusion

There are plenty of other intangible benefits to a high-documentation, low-meeting work culture. People who feel they have autonomy, independence, and time to do the stuff they care about most are generally happier at work. And happy people are more productive.

While it can be difficult to shake up the traditional way of doing things in favor of a new approach, switching away from a high-meeting, low-documentation culture can save companies a lot of time in the long run and open the door for innovative thinking.

Updated October 9, 2024